by Preston Griffith

Tchaikovsky(Right) and his pupil, the violinist Iosif Kotek(Left).

Tchaikovsky’s Valse Scherzo, Op. 34, composed in 1877, was his second work composed for solo violin and orchestra. The piece is one movement, Allegro Tempo di Valse, and is about six to nine minutes in length. The Valse Scherzo is dedicated to Tchaikovsky’s former pupil at the Moscow Conservatory, Iosif Kotek.

In 1877, Tchaikovsky had known Iosif Kotek for around six years according to a letter to his brother Modest Tchaikovsky, and he felt “a passion rages with me with unimaginable force” for Kotek at the time. He made a confession of his love for Kotek, but the love was not returned. The two talked about many things, including the piece Valse-Scherzo, Op. 34, which Kotek had ordered for a concert coming soon that year.

Tchaikovsky was also in the midst of composing his Symphony No. 4 and the opera Eugene Onegin in 1877, so he was very busy. Still, he managed to complete the Valse-Scherzo, and Iosif Kotek helped orchestrate the piece from his manuscript. The piece was also arranged for piano and violin. Kotek gave a private performance of the piece before the premier by Stanisław Barcewicz at the third Russian concert in Paris, 1878.

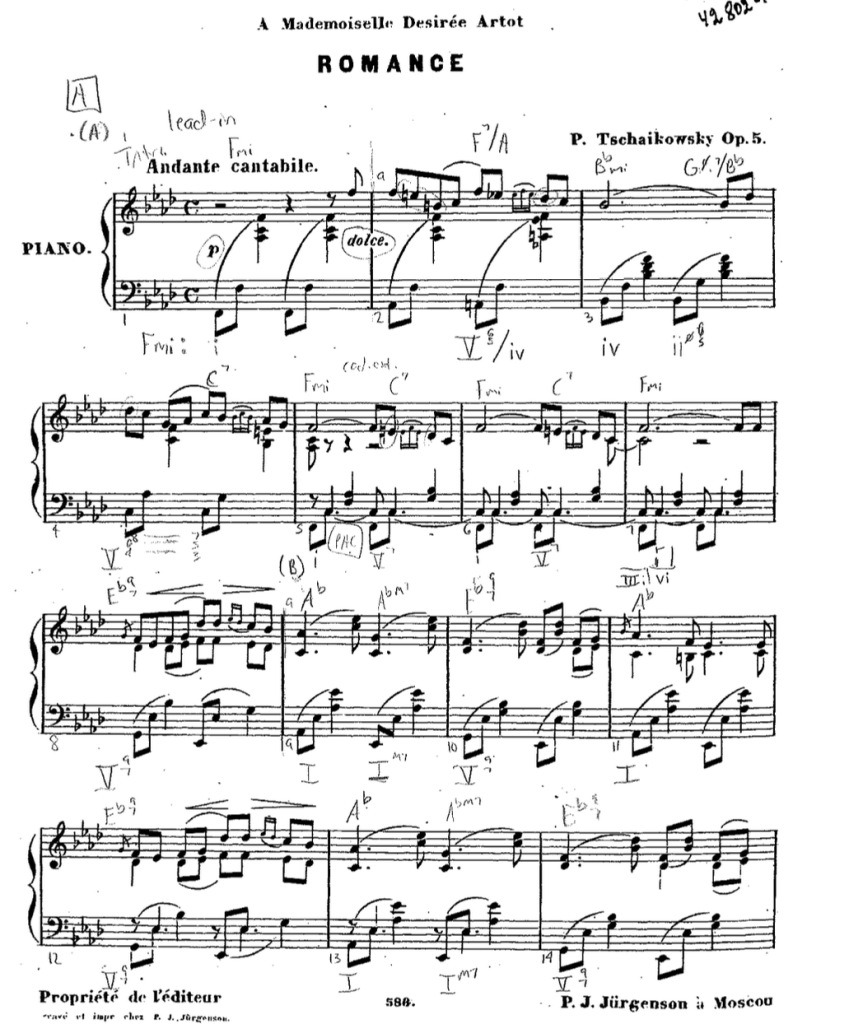

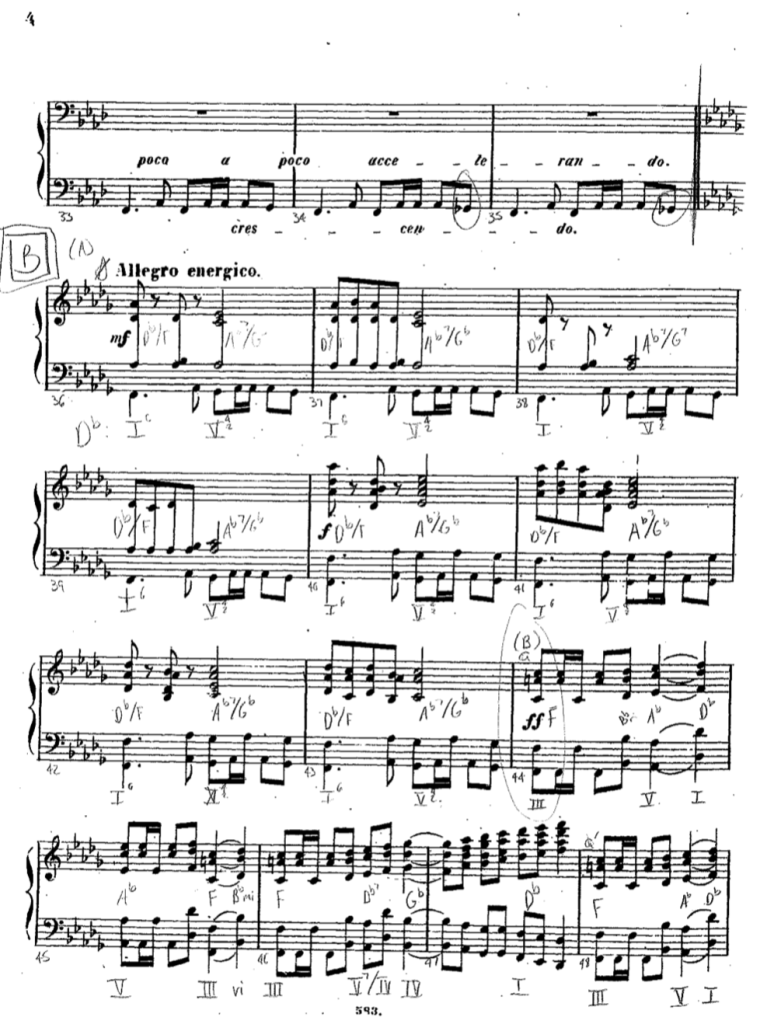

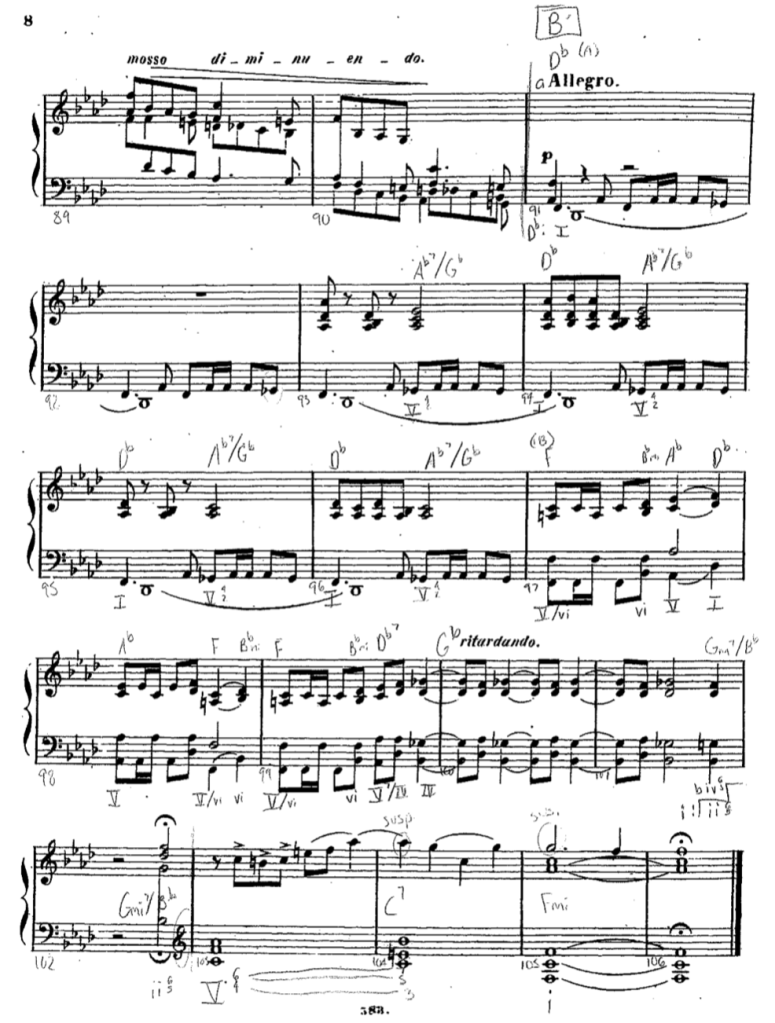

Right from the beginning, the piece has a bombastic effect in which the virtuoso violinist shows their skills. In C major, performance practice allows for the violinist to begin with a mixolydian ascending scale up the low G string reaching up to an A and play short eighth notes written with all down bows. The complicated techniques required to play the piece are recurring. The techniques span almost the entire range of the violin with the violinist’s fingers flying up and down the fingerboard. Complicated double stops are written for the soloist to play two or more notes at once, such as thirds and octaves that are very hard to keep in tune. As for bow technique, lots of spiccato, ricochet, and even upbow staccato are there to give the short, pecking kind of sound heard on the violin.

The Valse Scherzo sounds wild and powerful and one is not sure of it’s waltz nature except for the orchestral accompaniment (or piano accompaniment) playing the classic “boom chic chic” rhythm. The central section of the piece is more lyrical and showcases the sweet almost mystical effect the violin is able to produce with a soaring melody high on the E string. The piece has a large range of dynamics written, but is mostly played with a loud dynamic. Based on recorded performances, these dynamics are more of a color change than a change in volume. This is accomplished by playing the same notes higher up on a lower string to give a warmer tone color, or by varying the intensity of articulation or vibrato. No other instruments have a solo part in this piece.

Tchaikovsky’s Valse Scherzo, Op. 34 is another treat to listen to, and not common to hear given it’s technical difficulty. Iosif Kotek must have been an accomplished violinist to play such a work, and indeed asks Tchaikovsky in a letter at one point about studying with the famous Joseph Joachim in Berlin. Enjoy the two performances below of Augustin Hadelich playing the piano arrangement, and Itzhak Perlman playing the orchestral version linked below.

Citations

Brown, David. 2007. Tchaikovsky: the Man and His Music. New York. Pegasus Books LLC.

Tchaikovsky Research contributors, “Iosif Kotek,” Tchaikovsky Research, , http://en.tchaikovsky-research.net/index.php?title=Iosif_Kotek&oldid=74404 (accessed February 20, 2020).

Tchaikovsky Research contributors, “Valse-Scherzo, Op. 34,” Tchaikovsky Research, , http://en.tchaikovsky-research.net/index.php?title=Valse-Scherzo,_Op._34&oldid=68642 (accessed February 20, 2020).