By Preston Griffith

Could Tchaikovsky’s work have been taken from his own lived experience? To make a direct connection from his life experience to his compositions would be considered a biographical fallacy. Craig White, professor of Literature at University of Houston Clear Lake, defines the Biographical Fallacy as “the belief that a work of fiction or poetry must directly reflect events and people in the author’s actual experience.” If meaning were assigned to Tchaikovsky’s work only in relation to his life, then why would anyone want to listen to his music? In fact, many writers create characters whose thoughts and actions are completely at odds with their own. Making a direct connection to the author/composer’s life would only be a correlation the majority of the time, and that may be interesting itself, but without solid evidence from the original source explicitly showing the intent of the author, scholars will never be certain.

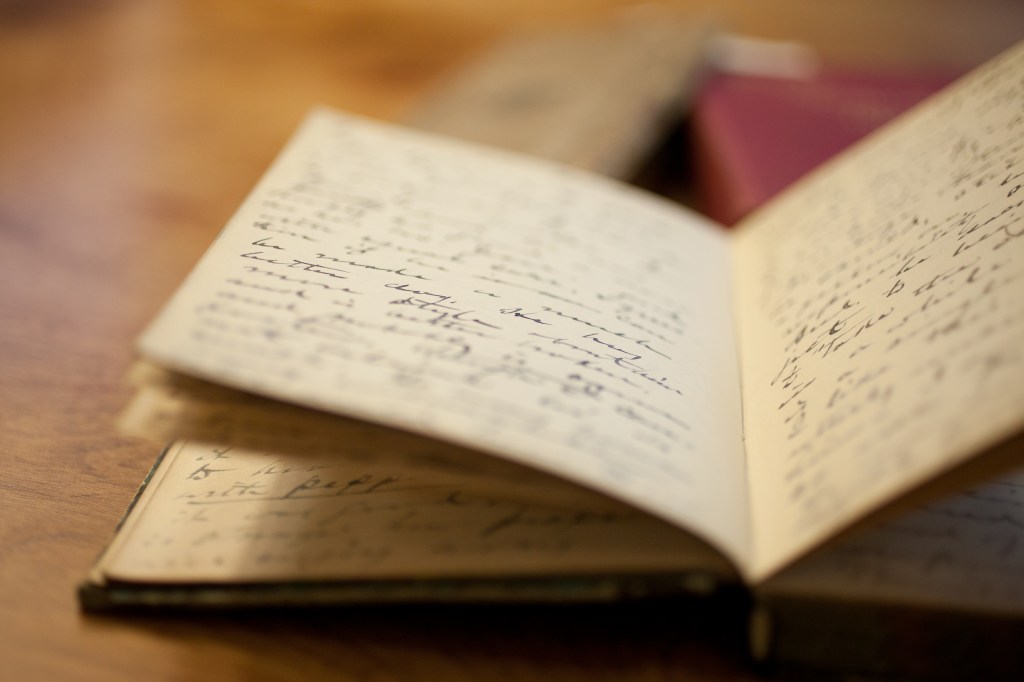

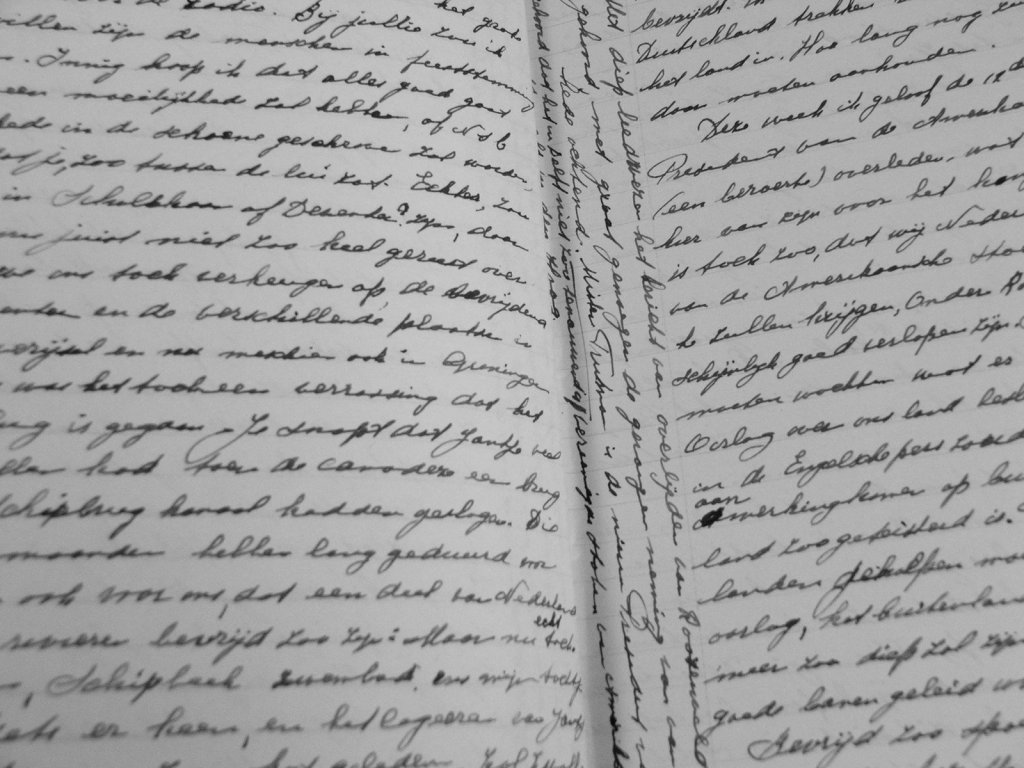

Tchaikovsky’s diary is often used as a source to find the relationship between his life and work. For instance, within his diary from April, 1884 to June, 1884, Tchaikovsky describes the events of everyday life, although much of his account is not usable. There are many unnecessary details that do not help music scholars as Tchaikovsky put so much detail into his diary, and much of what he said was simply observation. Many of these observations expressed his opinions, or at least implied them, but a large amount of them were unbiased accounts of the events that happened throughout the day. It may well be argued that there is so much detail in Tchaikovsky’s diary that the possible motivations or reasons for the creation of a composition are much harder to pinpoint.

The diary shows the events of Tchaikovsky’s life in 1884 on the estate owned by his brother-in-law and sister, Lev and Alexandra Davidov, at Kamenka in the province of Kiev. At the time, he was in the midst of composing his Third Suite for Orchestra, Op. 55. Most of his entries describe his daily routine which consisted of a walk (on which he would come up with ideas), work, tea, spending time with Bob (his nephew), dinner with family, and reading (English to practice the language, or other books of interest). For instance, on Sunday April 15 he wrote “Strolled in the garden and sowed the seeds not of a future symphony, but of a suite.” This shows scholars his location at the time of his Third Suite’s conception but does not give any indication of his motivation for writing one, or anything else for that matter.

He also wrote a lot about his emotions and how they changed, but several times his anger or general change in attitude did not seem to be due to any external circumstance. The game Whist made him angry as did some of the things his family would do or say. After coming to dinner on April 24 and finding that it was a new arrangement, Tchaikovsky writes “I suffered from hunger and lack of attention. It’s petty, but why conceal that even such a trifle can anger me?” This seems to confirm that Tchaikovsky has complex emotions and he was prone to fast shifts of mood. He also wrote a lot about the weather. Weather is known to change the mood of a person, but Tchaikovsky seemed to be making general observations. Perhaps it did subconsciously motivate him, but again, scholars have no direct evidence of this. Someone who is an expert at analyzing human behavior may be able to derive some motive for Tchaikovsky’s composition based on the details provided in his diary, but this would still only be correlation.

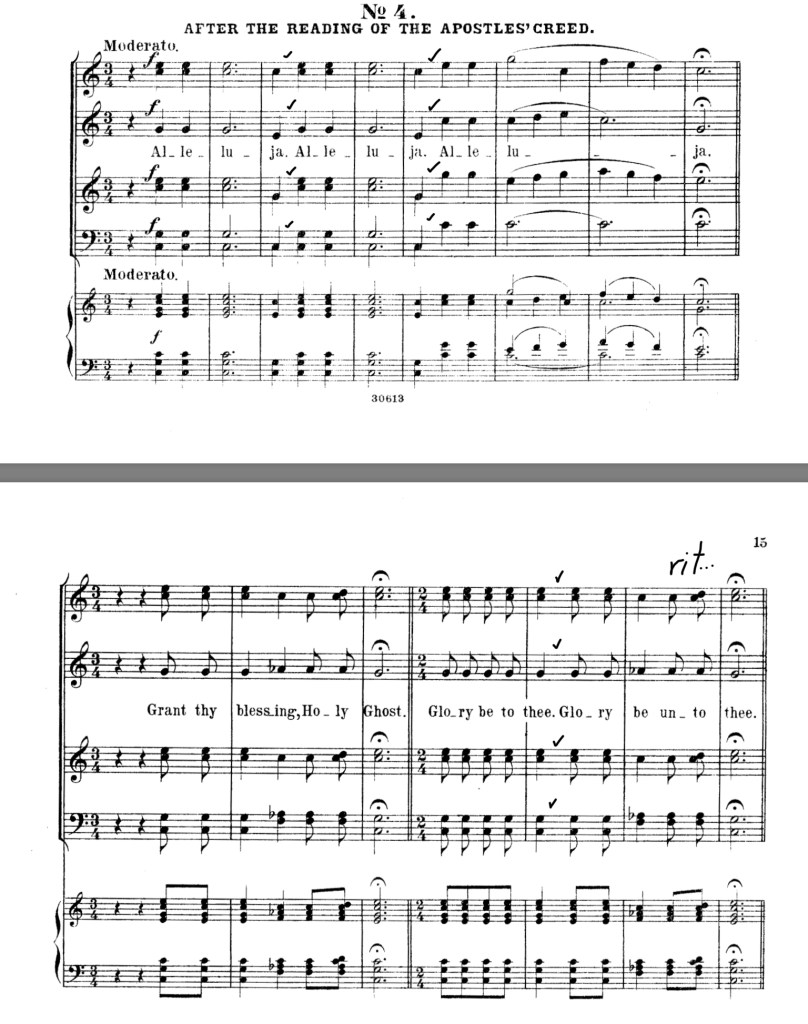

A diary is useful to music scholars as they learn that Tchaikovsky had a fairly normal life spent amongst family and friends and that he was not free from error. Little hints about Tchaikovsky’s composition process are given throughout, and a scholar may be able to produce an analysis of the time spent on his compositions and the kind of work Tchaikovsky did in order to create such masterworks. For example, he wrote “Fussed with one place in the andante until seven o’clock.” This was from the fourth movement of the suite. In this way scholars can see how work effected Tchaikovsky’s life, but not vice versa. There was only one clear inspiration for a composition within the diary. On the 18th of May, 1884, Tchaikovsky wrote “Played Mozart and was in ecstasy. An idea about a suite from Mozart.” This idea was later used to create the Fourth Suite for Orchestra, Mozartiana, written in 1887. Tchaikovsky was enamored with Mozart’s work and would often read about him or sit and play his works. On May 4 before he came up with the idea, he wrote “…sitting down to play Mozart’s Magic Flute in an extremely peaceful mood.”

In conclusion, trying to make a direct connection to Tchaikovsky’s life from his music results in a Biological Fallacy. Finding a correlation between his music and some aspect of his life may be interesting and possibly true, but as stated before, scholars will never be certain. Perhaps music scholars may not be able to glean some details that they seek to know, but in the process of reviewing the life of such a composer, perhaps they themselves would become inspired.

References

Tchaikovsky, Pyotr. “Diary Three: April 1884-June 1884.” Chapter 3 in The Diaries of Tchaikovsky. Trans. Wladimir Lakond. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1973.

White, Craig. “The Biographical Fallacy and How to Think Your Way Out of It.” University of Houston Clear Lake: Craig White’s Literature Courses. Accessed April 6, 2020. http://coursesite.uhcl.edu/HSH/Whitec/terms/B/BiographFallacy.htm