Andrea Davis

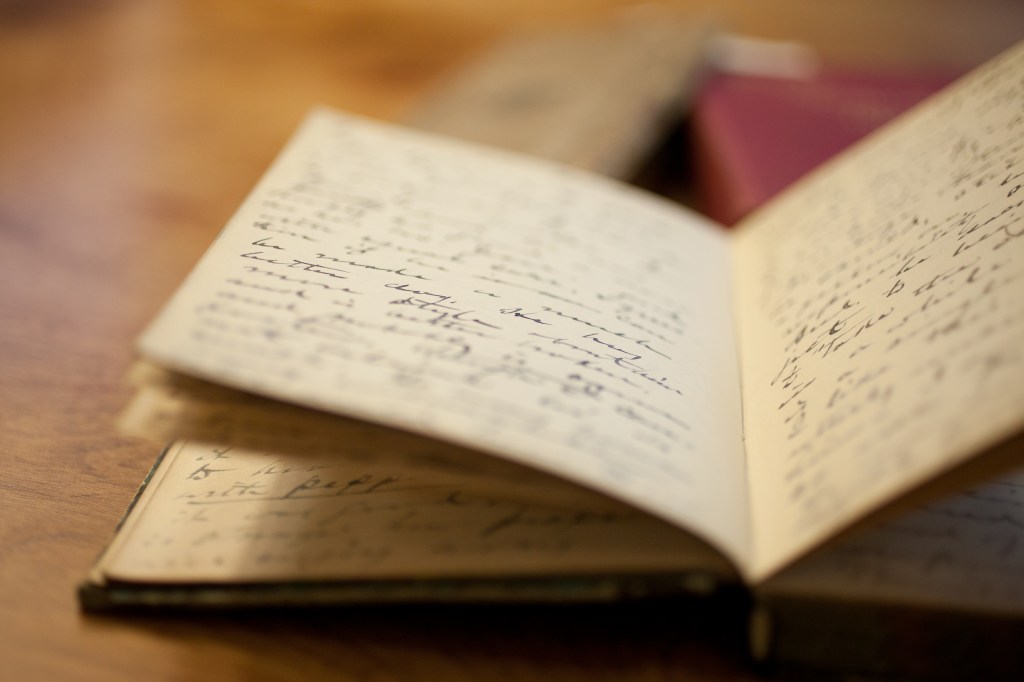

Tchaikovsky was a prolific writer. Years of his correspondence and diary entries have given scholars insight into his life and mind. While his personal writings communicate his thoughts and moods (and even occasionally his approach to composition), they do not necessarily present a lens through which his works can be understood. It is important to recognize the value of personal accounts and biographical details, but scholars must also understand that using these facts to make critical judgements may only serve to reduce the importance of an artist’s contributions.

The process of critiquing music or art through the lens of personal information often involves “Biographical Fallacy”. Craig White, Professor of Literature at the University of Houston Clear Lake, defines Biographical Fallacy as “the belief that a work of fiction or poetry must directly reflect events and people in the author’s actual experience.” Relying on biographical details to analyze a composition can lead one to develop a narrow view or to speculate about the artist’s intentions, which limits both the work itself and its potential interpretations.

When reading the letters and diaries written by Tchaikovsky, one might draw the conclusion that he was moody, emotional, and unhappy. He wrote, “I am in some kind of seething fury,” (26 April 1884), “I was irritable and found the opportunity to act hostile,” (3 May 1884), and “I am very weary,” (4 May 1884). If used to assess his compositions, Tchaikovsky’s statements could imply that his music has an undercurrent of anger or angst. In other diary entries, Tchaikovsky describes his appreciation—and irritation—of the changing weather, and also records his personal interactions: he is extremely competitive when playing whist, and he adores his nephew, Bob Davydov. While one can argue that the details, illnesses, and moods experienced throughout life could certainly influence a composition, the idea that creativity and understanding cannot surpass one’s experience is limiting. Tchaikovsky himself addressed this idea when he wrote, “Although I have a predilection for songs of wistful sadness, yet in recent years, at least, I…do not suffer from any want and I may, in general, regard myself a happy person!”

While biographical information as a tool for analysis is inadequate, the information itself is valuable. Our understanding of timelines, personal characteristics, and historical context can be broadened with an in-depth study of biographical material. Life experiences that illuminate a composer’s thought process or approach may be helpful when trying to compile a full and more complete picture of his works. Insights into moods and personal relationships can help one see a person’s humanity. The examination and study of biographical information contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of history and better scholarship.

Tchaikovsky’s letters and diaries are valuable sources of information for scholars and musicians. Learning about his life from primary sources can only augment one’s understanding of history and historical context. However, relying on biographical information to make assumptions about his works only serves to reduce the potential impact of Tchaikovsky’s creative influence and contribution to the arts.

Bibliography

Pozansky, Alexander. “Tchaikovsky: The Man Behind the Myth.” The Musical Times 136/1826 (1995): 175-182.

Tchaikovsky, Pyotr. “Diary Three: April 1884-June 1884.” Chapter 3 in The Diaries of Tchaikovsky. Trans. Wladimir Lakond. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1973.

White, Craig. “The Biographical Fallacy and How to Think Your Way Out of It.” University of Houston Clear Lake: Craig White’s Literature Courses. Accessed April 6, 2020. http://coursesite.uhcl.edu/HSH/Whitec/terms/B/BiographFallacy.htm

I agree with you about his temperament. I would never have imagined that he was not a happy person, or that his temperament depended on such simple things as the weather, however it makes sense since being a misunderstood person and who could hardly fit as a homosexual in society, I think it is a good reason to have such a temperament. On the other hand, I think that the intimate things of artists are a good tool to understand their work, since the artist can find inspiration in things as simple as “the weather.” I think biographical information is important, but as artists who work with feelings, I think a letter or a diary is invaluable.

LikeLike

I agree with your comparison of Tchaikovsky’s work to life experience and your commentary on his changing mood was especially thorough. Tchaikovsky’s music could be said to have “an undercurrent of anger or angst” as you stated, but this could not be the case because Tchaikovsky’s mood changed so much from day to day. His emotions were influenced by the smallest changes in daily life.

The most interesting concept you wrote was “the idea that creativity and understanding cannot surpass one’s experience is limiting.” I thought this idea was fascinating and made me ponder the origin of truly novel ideas. Creativity is a mystery, and it seems that human imagination is not limited by experience. How else would the classic works of fiction have been created with characters so different from the author? How would the famous inventions of the world come to be?

LikeLike