by Preston Griffith

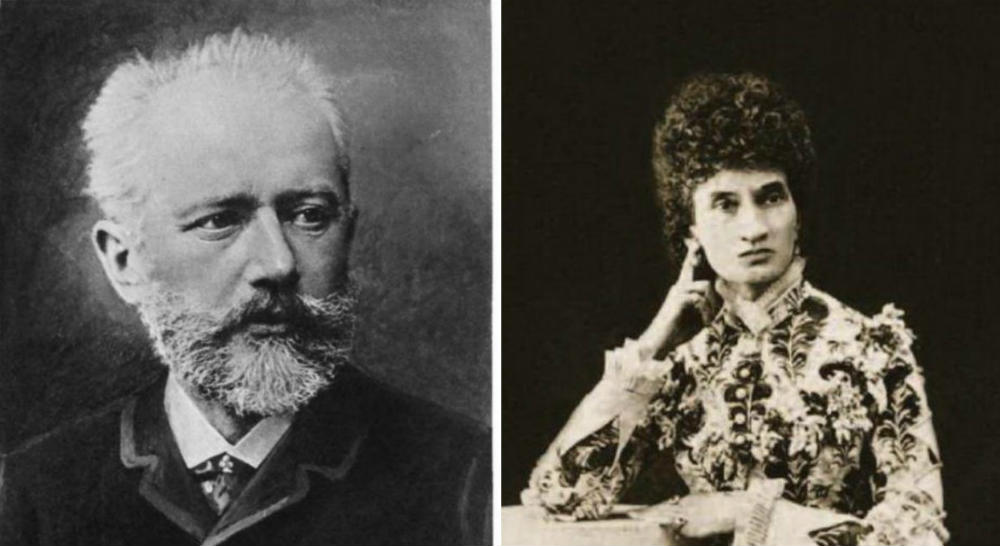

The relationship between Nadezhda von Meck and Pyotr Tchaikovsky began with correspondence in 1876. Tchaikovsky was age 36 and unmarried and had reached a turning point in his career. He was becoming dissatisfied with his job at the Moscow Conservatory, and had previously composed his first three symphonies and orchestral works like the Romeo and Juliet Overture, as well as operas like The Oprichnik and Vakula the Smith. The two were put in contact through the recommendation of Nikolai Rubenstein, the famous pianist and conductor, and Iosif Kotek, a violinist and Tchaikovsky’s beloved former pupil. Soon after, Nadezhda von Meck displayed a great admiration for Tchaikovsky’s music and became his benefactress.

Tchaikovsky and Nadezhda von Meck very quickly became friends through their correspondence and wrote some of their innermost worries and thoughts to each other. As early as Letter 13 Nadezhda von Meck suggested that their writing should come from an “inner urge” and not be all about “business matters”. By Letter 33, she had asked him to “write everything” about himself. Throughout Tchaikovsky’s marriage disaster and other bad situations, Nadezhda von Meck supported him and helped him recover. According to Edward Garden, “Both materially and mentally, then, Tchaikovsky’s relationship with Nadezhda von Meck during the first two years or so of their correspondence was all-important for his survival.”

Nadezhda von Meck was a curious and perceptive person, and asked Tchaikovsky many questions about his compositions and opinions on the popular music of the time. The two shared a similar taste in music, and they found comfort in each other’s thoughts regarding other composers and had intellectual conversation regarding technique and style. They were also both nationalist, well-read, and even shared similar thoughts on religion. Tchaikovsky enjoyed writing to Nadezhda von Meck as much as she did and wrote many a letters on subjects both trivial, and deeply philosophical.

Two letters, 13 and 178, provide a great example of the kind of relationship Tchaikovsky and Nadezhda von Meck had. To begin with, by the 13th letter, Nadezhda von Meck had requested Tchaikovsky to write as he pleased and to be frank with her. She expressed her admiration and gratitude for having such a friend, and this set the tone of the following letters. In Letter 178, Tchaikovsky writes of everyday concerns that show how intimate he was with Nadezhda von Meck and he even writes about the progress of his great opera, Onegin.

Letter 13 begins with “I thank you sincerely from the bottom of my heart, most respected Petr Il’ich, for the trust and friendship you have shown me in your appeal on this matter.” The tone is already one of admirations, and when she calls him “Petr Il’ich” she is addressing him in what is considered a polite, neutral form of address in Russia. She continues writing about her desire for him to write “as to a close friend who loves you sincerely and deeply” and wants Tchaikovsky to allow her to write him whenever she wants to receive a letter from him. She ends by comparing Tchaikovsky to a minister by saying “Pious people need ministers of their religion…But I need you, the pure minister of my beloved art”, and thanks him for dedicating his symphony to her. This letter is very important because it establishes Nadezhda von Meck’s desire for a deeper friendship with Tchaikovsky, and allows for their correspondence to become one of the most significant sources of information on Tchaikovsky’s life thereafter because of the wonderful resulting friendship.

In letter 178, Tchaikovsky writes about his delayed travels to Brailov, the residence of Nadezhda von Meck. He had become sick, and has various physical ailments such as back problems, and later in the letter writes about “attacks of lethargy”. By this point in their correspondence, Tchaikovsky is free to write about trivial matters in his life and is very descriptive. Staying in Verbovka, he writes that he has spent time with his niece Anna and Brother Anatoly. His Brother in Law’s niece had also come along and had romantic desire for Anatoly, but she was already engaged to another young man currently in school, and being tormented by these thoughts, wrote to him about it. Some drama ensued, but Tchaikovsky thought little of it, and everything was settled in the end.

In the most important part of the letter, Tchaikovsky writes “I played through the whole of Onegin to the people here yesterday evening. Their impressions were extremely favorable.” Letters like these were important, because they give the reader insight into the mind of Tchaikovsky, the composer. He goes on to say that he is afraid it is “impossible to perform” and that he is not sure what to do about the parts for Tat’ iana and Lensky. He had previously had the students of the Conservatory perform the opera as a trial run, but Tchaikovsky ultimately wanted the opera to be a well done show, and said “If the management of a theatre asks me for the opera, then I’ll be very demanding. There are lots of mistakes in the proof; I’ll have to do two proofs, but the opera will be ready by the middle or end of September.” With this, we see how Tchaikovsky is comfortable talking about his works with Nadezhda von Meck, and because she is a musician he can delve deeper into the small details of his works. In the end he writes that he looks forward to being at her house in Brailov, and that he is happy in Verbovka, but needs “to be without people from time to time.”

From the correspondence of Tchaikovsky and Nadezhda von Meck, one can gain a clear picture of the kind of relationship they had and enjoy information on the fine details of their lives. The two were very close friends and had a sincere love and admiration for each other. Tchaikovsky gained a benefactress, close friend, and confidant with his relationship to Nadezhda von Meck. She helped to make him the successful composer he is known to be today.

Citations

Tchaikovsky, Pyotr, and Nadezhda von Meck. To My Best Friend: Correspondence between Tchaikovsky and Nadezhda von Meck 1876-1878. Trans. Galina von Meck. Ed., Edward Garden and Nigel Gotteri. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993.

Both you and Omar mention that von Meck is the one who suggested their letters become more personal. I wonder if Tchaikovsky would have eventually shared personal things without her invitation? Because she was basically his employer, I wonder if he was worried about maintaining a business-type relationship, or if they would have become more personal and less formal over time regardless? At any rate, I like that they became friends. I agree with you that the perspective he gives into his compositions and thought processes is very valuable. I think it would be hard to be a composer that is so easily affected by the opinions of others, so it must have been nice for him to have a safe way to discuss his music.

LikeLike

We all have to agree that Nadezhda von Meck was the proactive one in their relationship. She urged Nikolai Rubenstein for Tchaikovsky’s contact information, and also asked Tchaikovsky many times to be more open to her about his person life and feelings. One thing that’s notable being overlooked by most people is the monetary support from Nadezhda von Meck to Tchaikovsky. This started with helping Tchaikovsky out of his personal debts, but this monetary support did not stop until the end of their relationship. They money given to Tchaikovsky was 10 times more than his salaries as a music instructor. I believed the monetary support played an important role in Tchaikovsky’s latter success. He will be struggling with his financial life for a long time and will not be able to focus on composing new pieces in his latter life.

LikeLike