By Aníbal Acevedo

In 1878 Tchaikovsky wrote a letter to Von Meck where he tells her how great he felt attending the regular Sunday Eucharistic celebration, and how he wanted to contribute writing music that will honor the most beautiful and important (as he mentioned) Liturgy in the Eastern Orthodox Church. Tchaikovsky thought that previous sacred composers (Bortniansky and Berezovsky) did an excellent job with texts, although their music was a little boring, and even though they followed the correct structure and style, it was time to make changes that allowed a different input. At the time, all musical compositions were under the so- called Monopoly of the Imperial Court Chapel, and it had to go under the music director’s approval to be published and presented, but according to Tchaikovsky, Jurgenson found a way to go around this impediment. This work is considered to be the first compendium of sacred music by an independent Russian Composer, and of course, for the monopoly that had been in place for the last two centuries this was unacceptable. After two months, Jurgenson decided to publish this work under the guice of a book, rather than a musical score, then filed approval in a different entity away from the Chapel and the people that were against it, but a couple of months later, in September of 1879 when they began printing, the Director of the Imperial Chapel intervened and confiscated more than a 140 prints; Jurgenson sued and won the trial. It is fair to say what a bold move this was, since the Liturgy had been premiered in a Chapel (with a worship setting) and Jurgenson claimed that the imperial Court Chapel had no business supervising the musical execution. The Liturgy was being performed more and more (1880) each time gaining new audiences who were both amazed and in disagreement with it. Ambrose, the Vicary, expressed his discontent saying that it was a sacrilege the way Tchaikovsky was using the high register, and some other comments on how it was too Italian-influenced. His composition was performed mostly outside Church, since it was approved by the Office of Censorship but not by the Court Chapel or its director, which allowed audiences to applaud and celebrate its magnificence. From here on, this important work helped defeat the Chapel’s Monopoly and set a new record that exhorted other composers to do the same, but Tchaikovsky’s Liturgy had a long way to go before it was properly liturgically performed again.

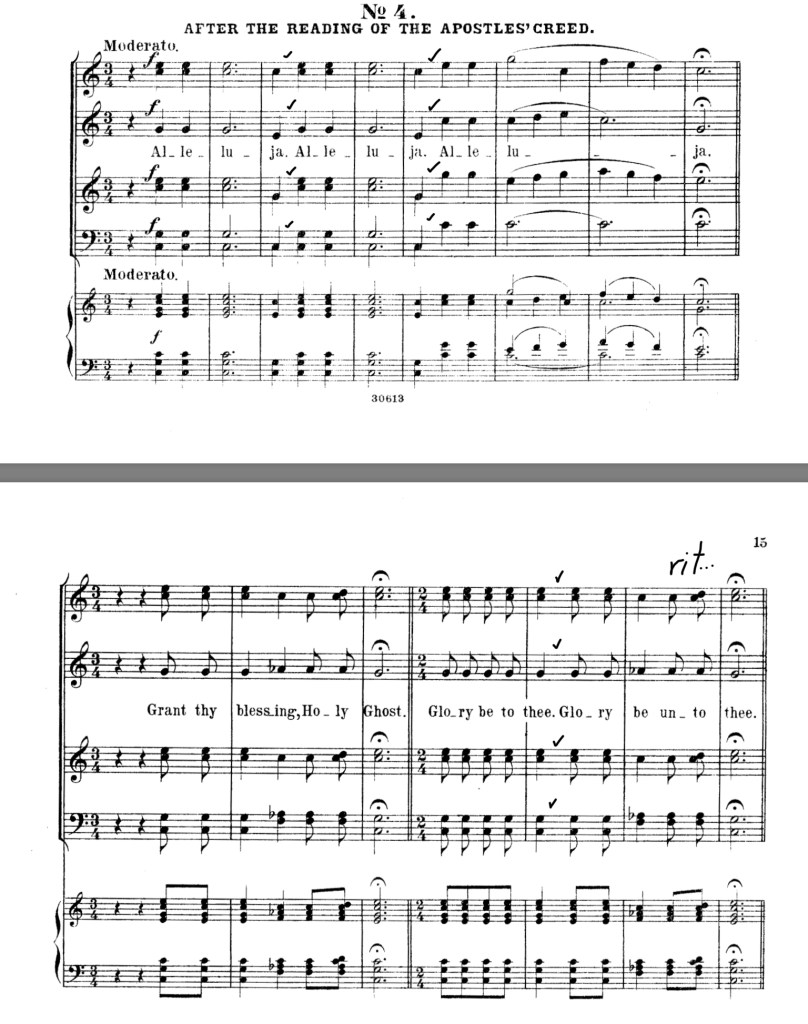

Musical Structure

Tchaikovsky wanted to maintain the standards of Orthodox Chorale a cappella music, and tried his best not to go far from it, taking the traditional Slavonic chants and presenting them in blocks of chords moving in the same direction (for the most part) with the occasionall imitation and polyphony shown in 2 of the 15 movements. The text is strictly taken from the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom in Russian, and it’s 50 minutes long.

The recurring way of how he used the higher register is just like any climax in an Opera (aria, ensemble or chorus), and as the Liturgy became well known, people talked about how this could be a distraction for eucharistic purposes, but in reality, it set a great contrast considering the simplicity and stillness of the whole pice, and above all, brought light and greatness to the composition. If we take under consideration his personal life, his failed marriage, and the nervous breakdown, we may say that the Liturgy was a vehicle to bring stability to this rough period.

References

Greenfield, Philip. “Horizons: Sacred Choral.” American Record Guide 83, no. 1 (January 2020): 190–91. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&site=eds-live&db=asn&AN=140408731. Accessed 15 May 2020.

Highben, Zebulon M. “Defining Russian Sacred Music: Tchaikovsky’s ‘Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom’ (Op. 41) and Its Historical Impact.” The Choral Journal, vol. 52, no. 4, 2011, pp. 8–16. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23560599. Accessed 15 May 2020.