Andrea Davis

Tchaikovsky’s three string quartets (the composition of a B flat first movement beginning in 1865, the third quartet reaching completion in 1876) were all successful, and it would seem that Tchaikovsky had an aptitude for the genre. His solo piano works, also successful among his audiences and colleagues, were smaller pieces meant for salon settings. Despite their popularity, Tchaikovsky spoke about his piano compositions with dissatisfaction. Although he may not have developed a personal style that could compete with pianists like Chopin or Liszt, Tchaikovsky’s piano repertoire is still attractive and engaging.

Souvenir de Hapsal is a cycle of three piano pieces that Tchaikovsky composed during a holiday to Hapsal (which is now present-day Haapsalu in Estonia.) During the summer of 1867, Tchaikovsky traveled to the resort town with his brothers, Modest and Anatoly, along with some members of the Davydov family. Over the course of the summer, Vera Davydov—sister to Tchaikovsky’s brother in law—developed romantic feelings for Tchaikovsky. Even though he did not return her feelings, Tchaikovsky dedicated Souvenir de Hapsal to Davydov. Souvenir de Hapsal loosely translates to “memories of Hapsal,” and the three short pieces that make up the cycle are, perhaps, little snapshots of Tchaikovsky’s holiday.

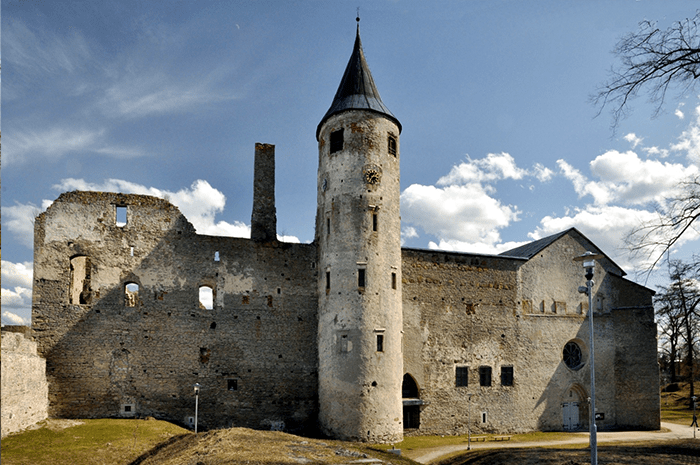

The first piece in the set is titled Ruines d’un chateau (castle ruins), and appears to be the lesser known of the three pieces. For the scherzo, Tchaikovsky reworked and used material from an Allegro he composed during his time at the St. Petersburg Conservatory (a practice he seemed to favor.) Chant sans paroles (song without words) completes the set. All three pieces follow a ternary A-B-A form. Each one is distinctive; they work as a set or as solo pieces. Ruines d’un chateau will be the focus for the remainder of this post.

As mentioned above, Ruines d’un chateau is in ternary form, and the different sections are highly contrasting. The A section, marked adagio mysterioso, makes use of an E minor melodic scale and is characterized by a I – V ostinato in the left hand. Two bars of open fifths serve as a small introduction before the melody begins. Each phrase in this section consists of 6 bars that end with a perfect authentic cadence. Each phrase is literally repeated before the melody develops into something slightly different—the use of chords and then the addition of tenor voicing rounds out the changes to the melody. Though there is no indication that Tchaikovsky based his melody on a folk tune, it has a very distinctive folk tune feel. The movement of the melody combined with the resolution of the cadences gives each phrase a quality of self containment, almost like the completion of a stanza or verse of a song. The A section ends by reiterating two bars of our phrase, but the motive ends on a D# and the resolution experienced in the preceding phrases is not to be found.

The allegro molto B section begins with a new tempo and time signature, and an abrupt shift to the key of C major. This new melody has the characteristic of a fanfare. The use of polyrhythms obscure the meter, and unusual harmonic progressions create a bit of ambiguity. Unlike the clear and closed cadences from section A, here the movement between phrases happens quickly and resolution is slightly elusive. The last six measures of the B section add even more harmonic confusion with the use of of a “C7” chord (spelled C-E-G-A flat-B flat), followed by a not-quite F# chord (spelled F#-A#-C-E), then finally concluding with a C major chord with an added F# (C-E-F#-G). The passage sounds virtuosic, but it is hard to establish a tonal center or real cadence.

The return of the A section brings with it the stability of the E minor I – V ostinato and the now familiar folk tune melody. This time, however, the left hand joins the melody of the right hand creating something of a round. Due to the overlapping melodies, phrases no longer end with perfect authentic cadences. Instead, the I – V ostinato produces a forward motion that continues through to the very end of the piece.

Ruines d’un chateau may not be a masterpiece, but it is not without it’s charms. The beautiful melody and harmonies from the A section, which stand in contrast to the exciting and dramatic passages of the B section, have definite appeal. Tchaikovsky successfully paints a picture of a castle—one can picture both the ruins of the present and the splendor of the past. The technique required for a performance should not be beyond the reach of competent pianists, and any of the pieces from Souvenir de Hapsal would be a valuable addition to one’s repertoire.

You can hear Igor Zhukov’s performance here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TN6-F0_vt5A

Bibliography

Tchaikovsky Research contributors, “Souvenir de Hapsal,” Tchaikovsky Resarch, http://en.tchaikovsky-research.net/index.php?title=Souvenir_de_Hapsal&oldid=68637 (accessed February 13, 2020).

Wiley, Roland John. “Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Il′yich.” Grove Music Online. 2001; Accessed 12 Feb. 2020. https://0-www-oxfordmusiconline-com.lib.utep.edu/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000051766.